America

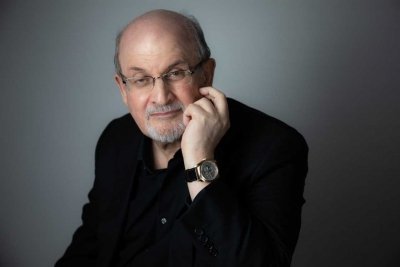

"Knife" is Salman Rushdie's account of his attack and subsequent recovery.

April 17 :

To be beautiful is to have an excuse to be, Emerson once said. On the other hand, just because something happened that was fascinating, strange, or scary doesn't mean it warrants a memoir.

Although Salman Rushdie's most recent autobiography was inspired by immense pain, it wanders aimlessly and is at times repetitive, despite the fact that the revered author is a lively and energetic (albeit inconsistent) writer. Unexpectedly dull, "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" deals with the horrific attempt on Rushdie's life.

The horror of the novelist's plight needs no explanation. The picturesque New York town of Chautauqua was his destination on August 12, 2022, for his scheduled speech on "the importance of keeping writers safe from harm." He has an excessive amount of knowledge on the subject: Since the publishing of his masterwork "The Satanic Verses" in 1988—in response to a fatwa demanding his execution issued by Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini—the author Salman Rushdie has gone into hiding multiple times. His decision to "remake a life of freedom," in his own words, in New York City was made only in the year 2000. He remained safe in America for twenty-two years.

Unfortunately, a 24-year-old radical from New Jersey named Hadi Matar stormed onto the platform and stabbed Rushdie multiple times before he could even start speaking at Chautauqua. He suffered serious psychological and bodily harm. According to his account in "Knife," he suffered a catastrophic injury to his left hand that cut all the tendons and a majority of the nerves. "My neck was pierced by at least two more deep wounds." The damage to his eye was the most distressing part. "The blade penetrated all the way to the optic nerve, rendering any hope of saving the vision hopeless."

Returning to full health was no easy feat. "When you're dealing with major injuries, the privacy of your body becomes nonexistent," Rushdie reflects. Every individual turns into a pawn that can be used by those around them. He describes how saliva was gushing out of his cheek because one of his facial knife cuts had severed the canal that normally carried it to his mouth. A young physician arrived to take care of this. While some nurses and physicians helped Rushdie use the loo, others extracted fluid from his leaking lung.

After physicians performed simultaneous operations on numerous organs during his emergency surgery, he was able to walk again fifteen days later. He returned to his Manhattan home more than six weeks later. Still, he had to go through physical treatment to regain control of his hand, and a cervical nerve severed rendered one side of his lower lip paralysed for life.

The protagonist, whom Rushdie chooses not to identify, had read very little of his work, as he says in the book's first chapter. "Whatever the case may have been, it was obviously not related to 'The Satanic Verses.'" What was the point of this book? I'll do my best to figure it out.

He follows through on this pledge in a lengthy section detailing his assailant's mental condition, which is a fictionalised conversation between the writer and the would-be killer. This exchange stands out in a book that mostly consists of well-rehearsed reflections on the suffering of oppressed writers - "if you are afraid of the consequences of what you say, then you are not free"; "when religion becomes politicised, even weaponized, then it's everybody’s business, because of its capacity for harm."

So, why does "Knife" appear so frequently? Mostly, it reads like an unembellished diary, a dryly documentary account. In the hospital, Rushdie has a blackout; he plans to go back to New York; he walks from the hospital to his flat; and on Valentine's Day, he and his wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, enjoy their first major nonmedical outing.

While Rushdie's citations of thinkers like John Berryman, Elias Canetti, and Henry James abound throughout "Knife," the author's own prose occasionally borders on cliche. The words of encouragement from his friends after the attack were "comforting and strengthening"; he is "making my peace with what had happened, making peace with my life" when he visits the scene of the crime. He compared his experience the night he met Griffiths to that of Ali Baba discovering the words that opened a treasure cave: "Open, Sesame." Then, with a blinding light shining on her, he saw the treasure: Griffiths. I have always believed that love is a force, that in its most strong form it can move mountains," he confesses, his confession the most nauseating. The world may never be the same.

Whenever Rushdie tries to be more experimental, he fails miserably. Especially in the embarrassing scene where the blade describes its own transgressions: "Here I am, you bastard...," his clumsy riffs on the knife's concept and image fall flat. I anticipated your arrival. Look at me. I'm staring you down as I plunge my assassin's blade into your neck.

In addition to exploring the broader implications of cruelty, the most effective parts of "Knife" delve into the psychological aftermath of the attack. "The victims of violence go through a profound shift in their perception of reality," Rushdie penned. Assaults like the one he endured "smash" the customary politeness. "The incomprehensible replaces reality, which dissolves." The attacker's motivations were so flimsy that they seemed completely unbelievable to Rushdie. According to Matar, he felt the victim was "disingenuous" when he committed the act. What Rushdie sarcastically calls a "unconvincing motive if one were to use it in crime fiction" is actually quite plausible. I find it fascinating that the author chose to picture a discourse with a more intriguing enemy.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of contemplation on the topics of violence, truth, and fiction. Aside from the stabbing, the pain, and the recovery, "Knife" mostly stays true to the facts. Not that Rushdie doesn't have any bigger ideas: The main problem is that everyone knows this by now, and his story doesn't really revolve on these issues. For example, he often gives scolding lectures on how stupid the younger generation is. "Something peculiar has transpired regarding the concept of privacy in our otherworldly era," he grumbles. For many Westerners, particularly young ones, it seems to have devolved into an unwanted trait rather than a prized characteristic. Nothing exists unless it is made known to the public. Afterwards, he scolds the "bien-pensant left," saying that their focus on minority rights has made "freedom of speech" less important. He doesn't bring up the "bien-pensant left" or explain how it relates to his clearly reactionary assailant. More like passing scoldings than protracted or even relevant arguments, these polemics are annoying.

Tragically, and maybe unfairly, the worst pain does not necessarily inspire the best prose. It is necessary to transform and elevate raw pain into something greater than itself. As given here, Rushdie's recollections are as crude and confused as a conversation. While it's reasonable that he would want to create a lasting tribute to his suffering, "Knife" does not live up to his best work or the suffering it was inspired by.