Literature

Chronicle of a war foretold? A century-old conflict and its lessons for today

After years of secret and not-so-secret alliances, bids to secure areas of influence and lucrative commercial deals, and even the odd land grab, war breaks out in one remote corner of Europe and slowly draws in other powers, big and small, near and far, till most of the world is caught up in the conflagration. Is it a description of what we are seeing in Ukraine now?

Not exactly. This was the state of Europe over a century ago, in the years leading up to the First World War. Of course, there are several differences in the situation and conditions then and now. which are inevitable, but there are also a lot of startling similarities, especially where mindsets, aspirations, and choices of statesmen (there were all men then) are concerned.

This aspect -- how attitudes and perceptions influence our choices and what consequences they might lead to -- is what we need to study and learn from.

And that is where history, usually dismissed as an academic subject or contested and distorted for political gain, comes in to help. "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it," philosopher George Santayana had observed as the 20th century dawned and his words still ring true as nations, who do not even have a remote stake in the ongoing Russian-Ukraine conflict, are impacted -- with the resulting ramifications and reverberations for their people.

We all know "what" happened due to the First World War -- the social and political upheaval as four mighty empires crumbled, the rise of ideologies like an assertive, and even, strident nationalism, leave alone communism and fascism, and the loss of an almost entire generation of not only the best and the brightest, but the capable and essential, among the other outcomes, that would result in a more ruinous and destructive war just two decades hence.

Also known is "why" the war broke out -- a complex chain of threats and actions and counter-threats and counter-actions following the assassination of the Austrian Archduke -- and heir-apparent -- Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.

However, as two insightful contemporary historians contend, it is "how" World War I began that we need to know and draw appropriate lessons from for the here and now.

Let's see these two books first, and a few other related works.

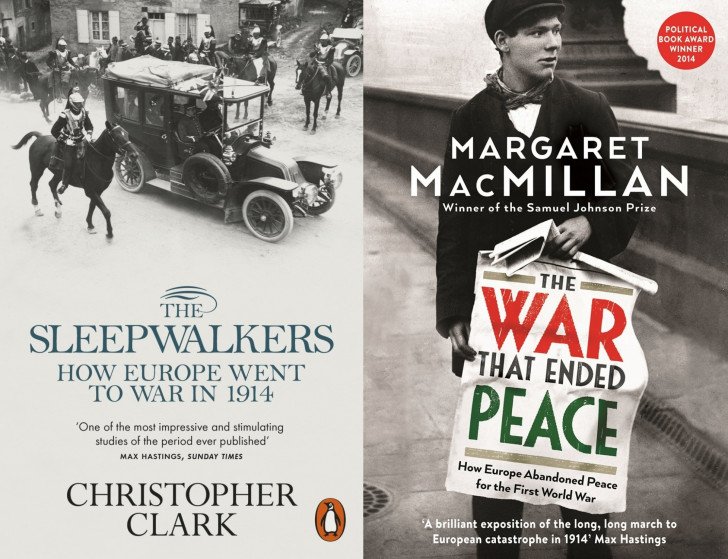

UK-based Australian historian Christopher Clark's "The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914", came out in 2012, two years before the WWI centenary but more significantly before this year which also saw a semi-violent regime change and consequent territorial annexation that gradually developed into what we are seeing in Ukraine today.

Clark provides an engrossing account of the causes of the war -- some stemming back into the previous century. The historian, whose area of expertise is modern Germany, and whose works include "Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947" (2006) and "Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Life in Power" (2000), shows why "how" is more important.

"Questions of why and how are logically inseparable, but lead us in different directions," Clark writes. "The question of how invites us to look closely at the sequences of interactions that produced certain outcomes. By contrast, the question of why invites us to go in search of remote and categorical causes."

And this, Clark points out, may bring a "certain analytical clarity" but has a "distorting effect, because it creates the illusion of a steady building causal pressure ... political actors become mere executors of forces long established and beyond their control".

His account does begin with a royal assassination -- though not of the Austrian Archduke, but of a higher potentate, Serbia's King Alexandar and his consort in 1903, to focus on the relationship between the two principal protagonists -- Austria-Hungary and Serbia -- whose quarrel led to the war, before going to ask four seminal questions, including one concerning what led to the polarisation of Europe into two opposed blocs, and why an international system that seemed to be entering an era of detente produce a general war?

But as Clark contends, the events of the month preceding the war's outbreak only make sense when one doesn't simply revisit the sequence of prior events, but "we need to understand how these events were experienced and woven into narratives that structured perception and motivated behaviour".

Don't these evoke a resonance now when we see the Russian-Ukrainian conflict?

Equally significant is Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan's "The War That Ended Peace: How Europe Abandoned Peace for the First World War" (2013) as it also predates this watershed year of 2014. It also follows the same trajectory as Clark, in examining how the continent that deemed itself as the epitome of global civilisation could descend to such barbarity as she sketches in her introduction.

MacMillan, who also reveals her own personal connection to the "dark and dreadful chapter in our history" -- noting how both her grandfathers fought in the war -- one in the Middle East with the Indian Army, and the other as a Canadian doctor in a field hospital on the Western Front -- goes to question what could have led to this outcome.

And she notes that there are many reasons cited -- the arms race, rigid military plans, economic rivalry, trade wars -- but also trans-border movement of ideas and emotions, including "nationalism with its unsavoury riders of hatred and contempt for others; fears, of loss or revolution, of terrorists and anarchists; hopes, for change or a better world; the demands of honour and manliness which meant not backing down or appearing weak ... ."

Don't all these appear familiar now too?

But MacMillan, whose other works include "Women of the Raj: The Mothers, Wives, and Daughters of the British Empire in India" (1988), "The Uses and Abuses of History" (2008), and "War: How Conflict Shaped Us" (2020), notes that while "forces, ideas, prejudices, institutions, conflicts" are relevant, so are the individuals.

"It was Europe's and the world's tragedy in retrospect that none of the key players in 1914 were great and imaginative leaders who had the courage to stand out against the pressures building up for war," she maintains.

She also notes how to claim the war was inevitable "is dangerous thinking, especially in a time like our own, which in some ways, not all, resembles that vanished world of the years before 1914".

MacMillan notes, stressing how the pre-WWI gambit of bluff and counter-bluff easily changed from a game to reality: "Our world is facing similar challenges, some revolutionary and ideological such as the rise of militant religions or social protest movements, others coming from the stress between rising and declining nations such as China and the United States. We need to think carefully about how wars can happen and about how we can maintain the peace."

Anyone who wants to study the detailed happenings of July 1914 should pick Gordon Martel's "The Month That Changed The World: July 1914 and WWI", where he says he doesn't want to present another book on the origins of the war, or point a finger at who caused it, but to just trace "how it happened: how those responsible for making fateful choices -- the monarchs and politicians, diplomatists and strategists -- grappled with the situation and failed to resolve it without war."

All this should have plenty of lessons for contemporary politicians -- and us.