Articles features

A Newly Illuminated Ramayana in Sita’s Light

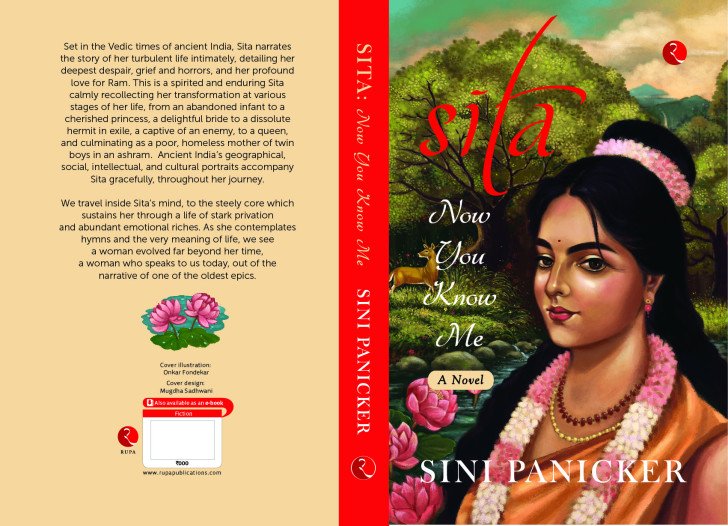

Panicker straddles the ancient and new worlds so well in Sita: Now You Know Me

Like most Indians, I grew up hearing stories: folk tales, literary stories, and of course mythology.I was deeply impressed by my seven year old sister’s reading all of the Kritivaas Ramayan in Bengali, and by the vigorous discussions that ensued, analyzing conduct, motives and outcome of actions. This is what Valmiki no doubt intended; as Sini Panicker says, “Valmiki knew exactly what he was doing†(311). In this remarkable retelling, Sini Panicker, scientist-turned-novelist seems to have distilled a life’s worth of mulling over the meaning of the Ramayana and decided to let Sita tell her own story in Sita: Now You Know Me. And indeed we do know her much better thanks to her compelling narrative.

In the God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy points out that there is only one story, a human story;“...the secret of the Great Stories is that they have no secrets. The Great Stories are the ones you have heard and want to hear again. The ones you can enter anywhere and inhabit comfortably. They don’t deceive you with thrills and trick endings. They don’t surprise you with the unforeseen. They are as familiar as the house you live in.†And so, Ms. Panicker’s novel is best considered a variation of a theme, but none the less valuable for it. A new light, a new angle, and the whole is illumined as never before. This time Sita gets to tell her own story.

Like much of post-colonial writing, it is the turn of the “Other†to speak, and she has much to say, yet it is said quietly, with dignity. This is not Bertha burning down Rochester’s house, or Helen-- that other abducted princess for whom a war is fought--disporting herself as she is systematically recast from Shakespeare to Alejo Carpentier. Hers are not the “invisible bullets†that Greenblatt said the silenced use to counter hegemonic representations of themselves. It is not likely to annoy the Hindu Right, as did Prof. A.K. Ramanujan with his landmark essay “300 Ramayanas†and be thrown out from any curriculum that incorporates it. Nor will it offend Hindu sensibilities as happened with the audience in Queens, N.Y at a performance of Sita Sings the Blues.

Rather it is a profoundly human Ram and Sita. With keen psychological insight, she shows us real people as they love, and suffer, and hope and choose actions without benefit of foreknowledge of how things will turn out. Sita agrees to attend the yagna in Ayodhya with her sons and Valmiki, with the expectations that they will all return to the Ashram; “The time had come again for a decisive moment. In the finite segments of one’s life, only a few solid, crucial moments occur for making life-altering decisions. However, the jester that my life had been, the decision was not mine in the end†(314).

And so it goes, things not always working out. How deeply this speaks to each of us. We’ve all made plans, had dreams, and loved others, only to be defeated by the “jester†as she calls it. Sita is raised and cherished by King Janaka and Queen Sunetra to be a confident, intellectually precocious, possible future ruler over Videha. She is loved by all, sister and cousins alike. She is not naïve; “The Swayamvar is usually a rigged game, where the daughters are just pawnsâ€

she knows (26). Yet, she falls in love and gives up those plans; “I had utterly lost myself…but found him†(41). What had she won? Banishment-- twice, hardship, humiliation and mockery. But also transcendent joy in her husband, and her sons.

But Panicker does not only explore the human dimension. Sita is also Earth-daughter, born in a furrow, returning to Earth mother when she dies. Like other mythic figures—Prosperpineabducted by Pluto—she is part of the vegetative cycle of “eternal returnâ€, bhumi-puthri. Her images tend to be horticultural; “Queen Kaikeyi…was like a parijatha tree. Ornamented with gorgeous crimson flowers, the tree is an alluring beauty from afar…An instinct to hug the beauty is instantly quelled, upon closer observation when the sharp thorns on its trunk are revealedâ€(94). She finds solace among the Ashoka trees in Lanka. And later in Valmiki’s ashram, she rediscovers her true identity—not a princess, not an ascetic, “I found my way back to [mother earth]†(200). Although the author avoids the Agni-pariksha, we know Sita is also Earth, Water, Fire and Wind and immune to the burning. She is a practical gardener and lover of Nature, who understands farming and herbal medicines. Her enormous resilience, the Ultimate Survivor is not the gendered equation of woman and nature, and as opposite of rational maleness. It is self-possession. It is mature acceptance of mistakes and bad decisions. Even a wry humor; “Once again, within a year, I had become an ascetic. It seemed to be my true calling†(290).

Another source of strength that helps her survive her ordeals are other women. Mother figures, sisters, Lopamudra, even Mandodari are her solidarity group. She derives great nourishment from them. They restore her sanity, her sense of self. She is able to tell Lopamudra her thoughts she barely acknowledges to herself. Doing simple tasks of helping in the kitchen releases a flood of stored memories: her mother, the women philosophers, the inimitable and brilliant Gargi. They remind her how fortunate she was to have been raised in an “era of spiritual investigation into the purpose of life and the eternal, sacrosanct laws of nature†(169). The irony of course is that their troubles also originate from two women, another trope from ancient myth, Pandora, Eve, Kaikeyi, Shurpanakha.

Finally, there is the legendary aspect to both Ram and Sita. They are born through divine agency, and have destiny to fulfill. The story of the Ram and Sita is not simply the sad story of star-crossed lovers, they are an Udharana, a paradigm of love. Valmiki helps Sita to give up her individual identity, to let go her ascetic concealment and approach Ram for the last, but also eternal time:

I am He and you are She

I am the Song and You are the Verse…

Valmiki tells Sita that her story will live on “as long as the Ganga and the Tamasa flow†(310).

So she is both human and divine; we know her but also find her unknowable. This tension animates the whole retelling. Ram is clearly flawed. Like any devoted wife, Sita is devastated by his harshness, his unreasonable anger, his banishing her rather deviously, making Lakshman do his dirty work. But we are never in doubt, despite his almost quixotic loyalty to the given word, the refusal to take an easy out (why not let Hanuman rescue Sita????), in the name of the “fair fight†of a warrior code, his extraordinary refusal to take Sita’s side over the gossiping crowds in the name of kingly duty, that he is divine too. Like Sita who loves him to the end, we must love Ram too. And suffer with them. The countless version of Ramayana from India to South East Asia in song, dance drama, and poetry have all fallen under their spell. Like Radhaand Krishna, they are more than a couple to whom Valmiki wanted to give “a very happy ending†(312); they are one.

This well-worn story comes alive fresh and heart-breaking in Panicker’s wonderful book. Read it and weep, and smile and say, “I’ve been there.†Isn’t that what good literature is supposed to do?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Manjari Chatterji was born and raised in India among loving family and book lovers. Her adult life has been spent in the States, raising her own family and teaching English at University of Wisconsin for over thirty years. Her interests are in Post-colonial Studies, and the ecology of food systems. After retirement, she has published a book of short stories, and has written a novel set in British India. She spends time with family, her garden, and lately, on a pontoon boat.

9 hours ago

US approval of massive arms sale to Taiwan amid China tensions raises regional volatility

14 hours ago

India has seen transformational economic change in last 11 years, PM Modi tells diaspora in Oman

16 hours ago

Arjun Rampal opens up about his challenging transition from modelling to acting

16 hours ago

Sameera Reddy reveals how long it takes bananas to ripen naturally

16 hours ago

Karan Johar opens up about handling online trolls targeting him and his family

16 hours ago

Urvashi Dholakia shares how Komolika let her explore performance shades actors only dream of

16 hours ago

Harnaaz Sandhu breaks silence after nearly slipping at a recent event

16 hours ago

Randeep Hooda reveals what he really does during jungle safaris

16 hours ago

202 Indians recruited into Russian Army; 26 dead, 50 awaiting discharge: Centre in RS

16 hours ago

Delivery boy dies by suicide after public assault; Tripura Police arrest three from Assam

16 hours ago

'Shaped my journey': Stalin credits wife Durga for his success

16 hours ago

Kerala court orders return of actor Dileep's passport

16 hours ago

'Be alive to ground realities': SC refuses to entertain PIL challenged bottled water standards