Literature

WWII's most audacious act: Kidnap of a German general

It seems like an Alistair

Maclean novel - an enemy general is kidnapped from near his

headquarters, spirited through nearly two dozen checkpoints, kept hidden

from search for nearly two weeks and is successfully taken out of the

territory. But it really happened in World War II, and two junior,

amateur British officers - who had conceived the plan in a Cairo

nightclub - carried off the German commander of the Greek island of

Crete with support of the partisans.

It was an audacious plan

which has never been seen before in warfare - generals have been

captured but this was the first time one had been kidnapped, said

British author Rick Stroud who brings the incident to life in all its

nearly unbelievable details in "Kidnap in Crete: The True Story of the

Abduction of a Nazi General".

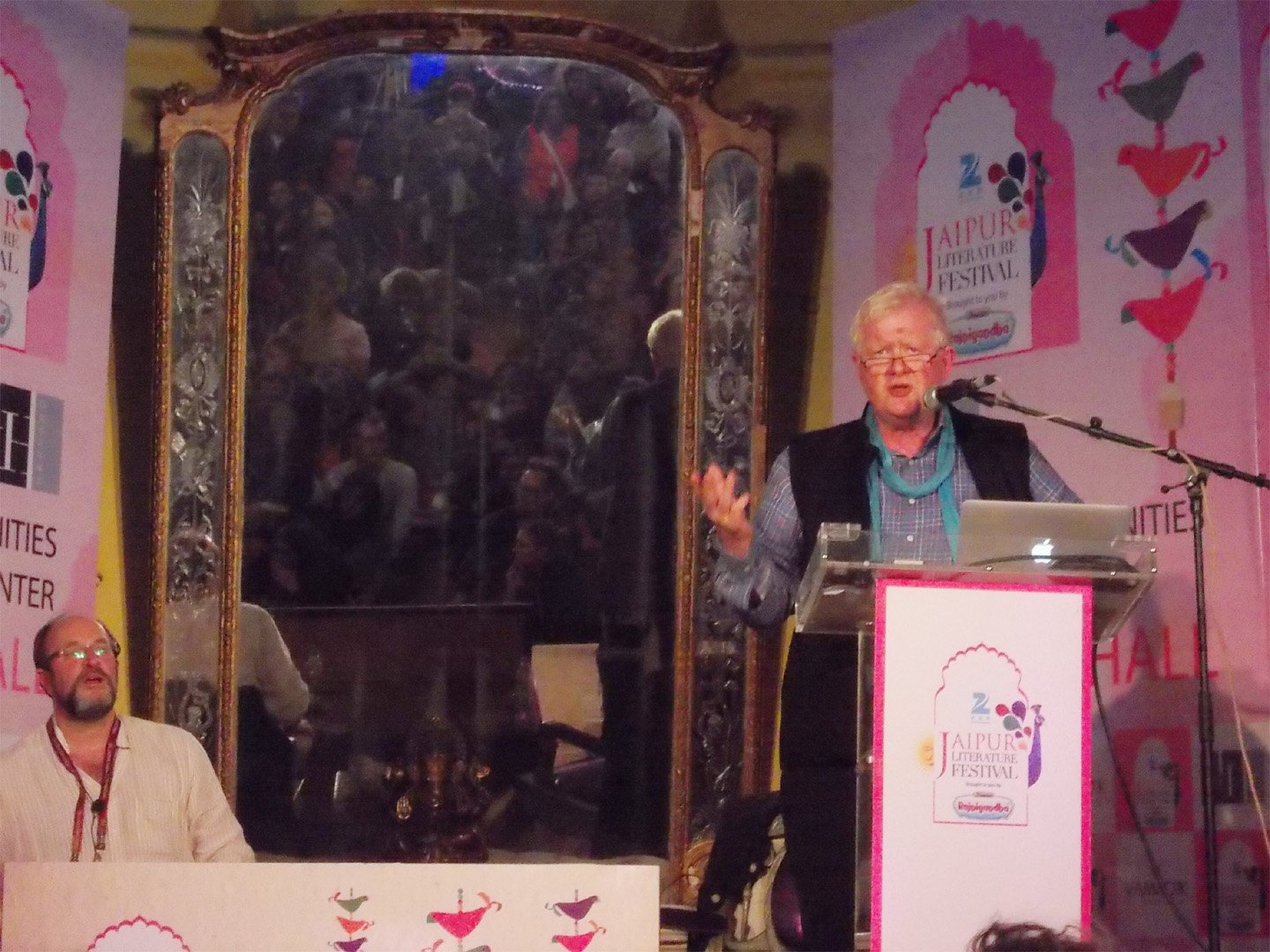

Speaking about the incident at a

session of the Jaipur Literature Festival 2015, Stroud said the two men

behind it were 29-year-old Major Patrick Leigh Fermor, known for walking

across Europe from Holland to Turkey in 1933-34 (writing about his

experiences four decades later) and 21-year-old Captain William Stanley

Moss, both working in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) who devised

the plan towards the end of 1943.

Leigh Fermor parachuted into

Crete in February 1944 but the others - Moss and two Cretan SOE

operatives - couldn't due to the cloud cover and only arrived on the

island two months later - in April 1944 - being dropped off by the navy.

"They had brought half a tonne of equipment including weapons, medicines and drugs - and suicide pills," said Stroud.

Though

the German commander they wanted to capture - Gen. Friedrich-Wilhelm

Muller, known as the "Butcher of Crete" for his brutal policies, had

been replaced in February by Gen. Heinrich Kreipe, who had been

transferred from the Eastern Front to a "cushy job" in occupied Crete,

the duo voted to go ahead, said Stroud.

"Little did Gen. Kriepe

know that when he took up his new charge that he was walking in a trap

and all his movements were being closely scrutinised," he said.

Leigh

Fermor during his time on the island had been busy carrying out

reconnaissance - while dressed as a Cretan shepherd, said Stroud, adding

he weighed a plan to snatch the German general from his residence but

dismissed as the place was too guarded and it was finally decided to

snatch him when he was travelling.

The plan was carried out on

the night of April 26, 1944 as Gen. Kreipe was returning home after

playing bridge with his subordinate officers - exactly at the point

which he had gauged as vulnerable for an attack.

"He was

delighted to see two German military policemen at that point. They

stopped the car and as he was reaching for his papers, one of them

(Leigh Fermor) yanked open the door, and pointed a pistol at him while

the other (Moss) coshed the driver unconscious. Gen. Kriepe violently

resisted capture and punched Leigh-Fermor in the face," said Stroud.

Moss

then drove the car while Leigh Fermor held the general unconscious and

they successfully passed through 22 checkpoints with the latter calling

out the "general's car" in German as they neared, he added.

They

abandoned the car with a message - intended to save Cretans from

reprisals - that the kidnapping had been carried out by British officers

and that "they were sad to abandon such a magnificent car", said

Stroud.

The team successfully evaded their pursuers till they

were taken off by a boat on May 14 - not without drama, when Moss could

not make the correct Morse code identification signal by torchlight.

Gen. Kriepe was taken to Britain and interrogated but nothing worthwhile

was obtained from him while the Germans carried out reprisals and razed

a village.

"Though a strategic and tactical failure, the

operation did have immense psychological impact as the news spread

around the world - even in German occupied territory as was a terrific

morale-booster," said Stroud.

Though both Leigh Fermor and Moss

have written personal accounts, Stroud says his is the most

comprehensive as it includes the Cretan accounts.

"In fact, when

Moss's 'Ill Met my Moonlight' was published, Kriepe - who had a bad

relation with him - successfully sued him for defamation and prevented

its German publication as well as release of the film based on it," he

said.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)