Articles features

Eva Peron’s tomb is too small for her ego (Travel with M.P. Prabhakaran)

(This is Chapter 2 from Mr. Prabhakaran’s book,An Indian Goes Around the World – I: Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum, which we started serializing recently.

see link for first chapter below.

Chapter 3: “Brahma and Laxmi Reincarnate in Brazil?†Read evey Monday. – Editor)

It was November 2001. I had been in Buenos Aires for five days, enjoying everything I saw around. I was surprised to see that, in spite of the economic woes the country as a whole had been experiencing, the capital city functioned fairly efficiently and its reputation as “The Paris of South America†remained intact.

Even before I arrived in Buenos Aires, the international media had been full of stories foreboding Argentina’s economic doom. At the same time as I was there, the International Monetary Fund was meeting in Ottawa, Canada, to explore ways of saving Argentina the embarrassment of defaulting on its debt repayment to lending institutions.

As it turned out later, the IMF’s efforts were of no avail: Argentina did default, in December 2001, on its public debt of US$141 billion, thereby besmirching its name in the comity of nations. Sovereign default is something no nation would find easy to live with.

In Buenos Aires and other major cities of the country, people took to the streets almost daily – demanding jobs, back wages, the money they had deposited in banks and, sometimes, even food. Riots resulting from the crisis claimed scores of lives.

When I was in Buenos Aires, however, the only visible signs of the economic gloom I noticed were empty tables in restaurants and occasional beggars on streets. Sometimes the beggars, almost all of them kids, approached customers in restaurants, too. I mean those restaurants that were lucky enough to have some customers. I saw a few beggars holding fliers with stories of their privation printed on them. Some customers would give them a coin or two without even looking at the fliers. Some others would shoo the intruders away.

One customer who gave a kid a small-size coin learned to his disappointment later that it was of five-peso denomination. The Argentine peso, at the time, was linked to the American dollar and equal in par value. The customer had stupidly thought that the smallness in size of the coin meant smallness in value.

Street Performers on Avenida 9 de Julio

There were also those who, strictly speaking, couldn’t be called beggars. Though their nuisance value was the same as that of beggars, they did provide some entertainment in return for what they were asking. They should be called street performers.

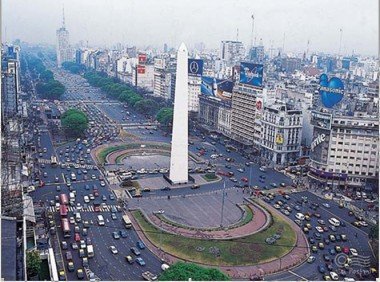

Most of them chose the widest avenue in Buenos Aires for their performance. The wider the avenue, the longer would be the traffic halt at pedestrian crossings. The widest avenue in Buenos Aires is Avenida 9 de Julio (July 9 Avenue). With 12 lanes, six each going in either direction, it is the widest avenue I have seen in any city anywhere in the world. The avenue is named after the country’s Independence Day. Argentina became independent from Spanish colonial rule on July 9, 1816.

The performers would wait at corners where Avenida 9 intersects with other streets and other avenues. As soon as the traffic light turned red, they would jump from the sidewalk onto the avenue, in front of the first row of vehicles, and begin their performance – juggling balls or sticks, torch display, dancing or just clowning around. They would have as much time for their performance as it took for pedestrians to cross the 12-lane avenue and its green-patch separation in the middle. A few seconds before the traffic light changed back to green, they would stop their performance and approach the occupants of vehicles with a hat in hand. I wondered whether those teen artistes and acrobats were able to make a living doing what they were doing. Most motorists ignored them, and some even stared and shouted at them.

After savoring the sights and sounds of Buenos Aires for five days, I felt that I hadn’t had enough. I wanted to see more of the city and surrounding areas. I wanted to visit San Telmo and watch the tango a few more times. So the day before I was scheduled to fly out, I went to the Varig Airlines office to enquire whether postponing my departure by a few days would cost me anything extra.

‘You Are No Gandhi’

I was sitting at the airlines office, waiting for my turn to be called at the reservation desk. The wait had become too long, and I was getting bored. I turned to a woman sitting next to me and asked whether she spoke English.

“What a relief!†I said when she replied yes. “Those who speak English are very few around here.â€

She threw a contemptuous look at me. I got the message: While my question was a legitimate one, especially in a country whose native language is Spanish, the remark I made in response to her reply smacked of superciliousness. How stupid of me to make such a remark! When I made it, I had in my hand a copy of Buenos Aires Herald, an English daily published from the Argentine capital. I should have known that it was published not for occasional visitors like me, but locals like her. I was relieved when she laughed away my faux pas and decided to continue the conversation.

“Are you from India?†she asked me.

I have heard that question from foreigners, especially those who are familiar with Indians’ features, umpteen times. But this time, it had a different effect on me. It came from a person living in a city where Indians are a rarity. I started liking her.

“Yes, originally from India, but now I live in the United States,†I said. That has been my stock reply every time I hear that question. I have lost count of the number of times I might have given that reply.

“I can tell, you are no Gandhi,†she said, her eyes narrowing into a squint. She was waiting for my reaction.

“You are absolutely right,†I told her. “If I were Gandhi, I would be living in India and doing something for the less fortunate there.â€

Gandhi was very much on her mind, she said, because she had just finished reading the Spanish version of Freedom at Midnight. She also said that she had been a great admirer of Gandhi since her childhood. “My admiration went up after reading the book,†she added.

Freedom at Midnight, by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, published in the mid-1970s, is a fascinating portrayal of India’s freedom struggle. Gandhi dominates the book from beginning to end. The Argentine admirer of Gandhi also told me what she thought about the other personalities that figure prominently in the book: Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Louis Mountbatten.

She thanked me

for correcting her, when she said that Mountbatten was the only one among them

who was still alive. “He died in 1979 in a bomb explosion,†I told her. “He was

sailing on his pleasure boat, off the coast of Ireland, when it happened. It was

found out later that the bomb had been planted on the boat by terrorists

belonging to the Irish Republican Army.â€

La Recoleta Cemetery

We talked about many more things. The blunder with which I started the conversation notwithstanding, a rapport began to develop between us. She gave me the addresses of a few must-see places in Buenos Aires and then asked: “Have you visited the cemetery of the rich and famous in Argentina?â€

She was referring to La Recoleta Cemetery, a visit to which is invariably included in all conducted tours of Buenos Aires. The cemetery is 13½ acres in area and considered the costliest piece of real estate in all of Argentina. It has rows and rows of mausoleums, built in memory of many famous (and infamous) people in Argentina’s history – presidents, politicians, soldiers, authors, etc. The size and showiness of the mausoleums are in proportion to the stations they held in life when alive.

I had already visited the cemetery. She fairly summed up my impression of the place when she said, “Couldn’t they have found a better way of spending that money?†Then she added, “What do you think of Eva Peron’s tomb?â€

“Too small for her ego,†I said. “Her ego deserved something as awe-inspiring as the Taj Mahal. And how presumptuous of her to expect us to cry for her!†I was alluding to the “Don’t cry for me†epitaph on Eva Peron’s tomb.

She burst into a big laugh at my allusion, and said, “I also had similar reaction when I read the epitaph.â€

By then, my turn came to approach the reservation desk. I was disappointed to learn that for every deviation from the original booking, I would have to pay 100 U.S. dollars extra. I gave up the idea of extending my stay. For a person traveling on a shoe-string budget, 100 dollars is not a negligible amount. The wonderful conversation I had with the fine Argentine lady helped me easily forget the disappointment at not being able to extend my stay in Buenos Aires.

After I left the reservation counter, I waited until she finished her work. I wanted to continue talking with her. I told her so and invited her to coffee, pointing to the McDonald’s around the corner. She said she had to rush to a job interview. She had lost her job as a chemist a few days earlier. “My husband is still employed. So we don’t starve,†she said.

But before rushing off, she managed to find just enough time to launch a tirade against McDonald’s: “Did you see the invasion of McDonald’s in this country? The beef the McDonald’s sells is an insult to Argentina. We have the best beef in the world.â€

She was

exaggerating only slightly: Argentina

is known for its high-quality beef and Argentines for their “compulsive

consumption†of it. The quote is from the late R.W. Apple Jr., who at the time

was an editor at The New York Times. His food reviews from around the world, which frequently

appeared in The Times, were as

delectable as the foods he reviewed. According to Mr. Apple, an average

Argentine’s annual consumption of beef was about 130 pounds, more than twice

that of an average American.

A Cow-Eating Hindu

My new Argentine friend told me not to leave the country without tasting the Argentine barbecued steak. “It’s world-famous and it’s genuine steak,†she said, placing her right palm on the right side of her waist to indicate where the meat for the steak came from.

Suddenly, she fell silent and looked upset. After a few seconds, she continued, with an expression of guilt on her face. “I am very sorry,†she said. “It’s beef. Please forgive me. Aren’t you a Hindu? I know the cow is supposed to be sacred for Hindus. Please, I didn’t mean to offend you.â€

The profusion of apology and expression of guilt made me say to myself that the cow-worshipers among my Hindu brethren had done a wonderful job. I placed my hands on her shoulders, looked straight into her eyes, and said: “You are looking at a cow-eating Hindu.â€

She broke into a big smile. I thanked her for the “wonderful conversation†and said goodbye.

Since

that day, she has been the second Argentine that comes to mind whenever I think

and read about Argentina.

The exalted first place is still held by Gabriella Sabatini, the tennis star of

the 1980s. The only complaint I had about Sabatini was that she grunted while

serving the ball.

(To be continued)

My Two Embarrassing Moments in Buenos Aires (Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum-1: M. P. Prabhakaran)

http://dlatimes.com/article.php?id=40709

An Indian Goes Around the World – I (Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum)http://dlatimes.com/article.php?id=40126