Articles features

Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum – But in Its Crude Form (Travel with MP Prabhakaran)

Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum

– But in Its Crude Form

M.P. Prabhakaran

(This is Chapter 8 from Mr. Prabhakaran’s book, An Indian Goes Around the World – I: Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum, which we have been serializing in this space. As readers can see, the main title of the book is taken from the title of this chapter. Chapter 9, “Capitalist Celebrations in Communist China – on May Day,†will appear next week. Read the series every Monday. – Editor)

Our 10-day tour of China officially began in Beijing, on a beautiful April morning, in the year 2002. Our first destination was the world-famous Tiananmen Square.

All the roads our tour bus wended its way through were crowded, mostly with bicyclists. There were rows and rows of them, at times taking up the entire width of the road, making it difficult for motorists to overtake. Eight million bicycles and 1.3 million automobiles, which 14 million Beijingers use, were jostling for space in the morning rush hour. It was quite a spectacle.

Tiananmen Square was a good half-hour ride from our hotel. But I was already there, mentally. The rich history of the square was only part of the reason for it. Tiananmen in Chinese means the Gate to Heavenly Peace. It was also the gate to the Forbidden City, which was the seat of imperial power in China from 1368 to 1911. During this long five and a half centuries, the country was ruled by emperors belonging to the Ming and Qing Dynasties, in that order.

It was at the gate of the Forbidden City that Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China, on October 1, 1949. Tiananmen Square was much smaller in size, when it was the courtyard of the imperial palace, than it is today. After the Communists came to power in 1949, they tore down most of the buildings around the courtyard that were used by imperial ministries. They expanded the courtyard into the sprawling Tiananmen Square that we see today. Today, it is large enough to accommodate 60 soccer fields. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), up to a million people used to parade through the square on ceremonial occasions, with a proud Mao Zedong on the review stand. When Mao died, in 1976, another million assembled there to pay him their last respects.

All those details about Tiananmen Square were impressive indeed. But my preoccupation with it, on that morning, had nothing to do with those details. It had to do with what happened there in 1989. In the spring of that year, the place was the nerve center of a pro-democracy movement in China. The movement that started in Beijing, in April, quickly spread to other major cities of the country. Tiananmen Square was the scene of daily demonstrations by students, demanding democracy and freedom. The immediate incentive for the demonstrations was a visit by Mikhail Gorbachev, then head of state of the Soviet Union. The Chinese students had already been inspired by the reformation of the Soviet Communist system, which Gorbachev had initiated through what were known as perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness). They longed for similar reformation in their country’s governing system. Quite coincidentally, the Gorbachev visit also became instrumental in the Tiananmen Square demonstrations’ being broadcast live to the whole world. The world media had descended on Beijing to cover the visit.

The Massacre of Demonstrators

But the activities in the square ended abruptly on the night of June 3, when the army moved in and massacred hundreds of unarmed demonstrators and injured thousands of them. According to a report, by Nicholas D. Kristof, that appeared in The New York Times of June 21, 1989, “The true number of deaths will probably never be known, and it is possible that thousands of people were killed without leaving evidence behind. But based on the evidence that is now available, it seems plausible that about a dozen soldiers and policemen were killed, along with 400 to 800 civilians.†At the time, Mr. Kristof was the Beijing bureau chief of The Times. He goes on to say in the same report: “…many people suspect that troops burned the bodies of many citizens to destroy the evidence of the killings. After soldiers sealed Tiananmen Square about dawn that day, a large bonfire could be seen coming from the square. While it may have been the tents and other remnants of the students’ encampment on the square, some fear it was also used to cremate the students’ bodies.â€

Of those who survived, thousands were arrested and charged with “counterrevolutionary†crimes. Most of them have served, and many are still serving, prison terms. Some were executed.

Thirteen years later, I was on my way to the scene of the tragedy. I couldn’t contain my anxiety. What I watched on television on that infamous June night in 1989 came back to mind: soldiers firing into the crowd; soldiers clubbing demonstrators until they collapsed; and, most vivid of all, a courageous young man defiantly standing in front of an advancing column of army tanks, carrying a bag of food for soldiers. The courage he displayed had captured the imagination of the whole world.

Thoughts about him and those who sacrificed their lives in their efforts to bring democratic change in China had taken me to a different world, when an announcement from our tour guide brought me down to earth. We were already in Tiananmen Square, the guide said.

Hawkers at Tiananmen Square

The square’s storied past suddenly disappeared from my mind when a crowd of hawkers swarmed us as we came out of the bus. They were young men and women from nearby villages who made a living peddling their wares among tourists. The crude and aggressive way they did it would put their counterparts in any capitalist country to shame. A few yards away from the vociferous hawkers was the famous Mao Mausoleum. The embalmed body of Mao, the father of Communist China, was lying in state inside the mausoleum.

China’s rapid growth in the capitalist world market may owe nothing to the Communist ideals that Mao preached. But it owes a great deal to his memory. Outside the mausoleum was a bazaar selling Mao memorabilia – Mao busts, bags, badges and musical lighters playing short renditions of “The East Is Red.†It also sold key rings, thermometers, face towels, handkerchiefs, address books and cartons of cigarettes. Mao – in case anyone wonders why cigarette was sold as part of his memorabilia – was a chain-smoker. About the commercialization of Mao’s name, a commentator has this to say: “Mao might have ruined the Chinese economy, but sales of Mao memorabilia are certainly giving the free market a boost these days.â€

The hawkers continued to pester us. They shoved their merchandise in our hands and shouted: “Five dollars,†“Ten dollars,†“Eight dollars.†The price was what they fancied at that moment. But there was no fancying about the currency in which they wanted the transaction conducted. It was the Almighty American Dollar, not the Chinese yuan. They wouldn’t take no for an answer. They kept insisting that we quote our price if we didn’t like what they were asking.

Repeating “How much, how much,†they followed us all the way up to the gate of the Forbidden City. There they stopped, not because of any fear of Mao, whose huge portrait overlooking Tiananmen Square was hung over the gate. They stopped because they wouldn’t be allowed inside the gate unless they paid the entrance fee.

The Forbidden City

The Forbidden City is called so because, until 1911, entry into it was forbidden to all, except those who were on imperial business. Today, the Chinese government touts it as a great tourist site and prefers to call it the Imperial Palace or the Palace Museum.

Once inside the Forbidden City, we felt greatly relieved. We were relieved that the hawkers were no longer trailing us. We were also excited to be in an entirely different world – the world of the 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, their eunuchs, their concubines and their superstitions. The pleasure-loving emperors rarely came out of their inner chambers. The business of running the empire was mostly left to their favorite eunuchs.

The architecture of the Forbidden City abounds in symbolism. The dragon was the imperial symbol, red the imperial color and nine the imperial lucky number. The red door of the Gate of Supreme Harmony, the main entrance to the Forbidden City’s central courtyard, has nine rows of nine nails. The Forbidden City, we were told, has 9999 rooms. We could think of a few better things to do than visit them all to confirm the number.

But we did visit the most important ones, like the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Hall of Medium Harmony, the Hall of Preserving Harmony, the Palace of Heavenly Purity, the Hall of Union and Peace, and the Hall of Earthly Peace. Each hall was associated with a particular function of the emperor. For example, it was in the Hall of Preserving Harmony that the emperor held banquets and, during the Qing Dynasty’s rule, conducted rigorous civil service tests for appointment to various government positions. The highest scorer in the test also became the son-in-law of the emperor.

We also made it a point to visit the dwelling area of some of the concubines. Their tiny rooms – and the tiny beds, tiny tables and chairs, and tiny shoes – made us wonder how tiny they themselves might have been. “How could such tiny beings satisfy imperial appetites?†I asked my friends in the group.

After wandering through the Imperial Garden at the northern end of the palace, we came out through the northern gate, the Gate of Divine Prowess. There was nothing divine about what we encountered outside the gate, though. It was very worldly: Another group of aggressive salesmen was waiting there to pounce on us. This group was selling not goods, but service: a quick massage while we were waiting for our bus. Each salesman was carrying a folded chair. There was no saleswoman among them and so the six women in our group were spared the harassment. The masseurs concentrated on the three men. “Sit, sit,†they shouted, pointing to the chair, “one dollar, one dollar.â€

“The price is right,†I told my friends, “but not the time and place.â€

After a few minutes’ pestering, they gave up on the two American males and started concentrating on me. Being the only Indian in the group, I might have struck them as an easy target. When the pestering became too much, three women from our group came to my rescue. They formed a protective circle around me and one of them said, “I won’t let my husband spend any more money today.â€

That didn’t work either. One of the masseurs found that a small area of my buttocks was still unprotected. He reached for the area with one hand and started massaging it. With the other hand, he opened the chair and placed it close to my rear end. “One dollar, one dollar,†he kept shouting, “sit, sit.â€

Fortunately, our bus arrived before he could force me to sit on the chair. All of us hurriedly got on the bus. I heaved a sigh of relief. “Ladies and gentlemen,†I said to my friends, “democracy might not have come to Communist China, but capitalism has. It has come all the way up to Mao’s mausoleum, but in its crude form.â€

They had a good laugh.

Photo-1:

A nine-member tour group from the U.S., of which the author was one (seen at the extreme left), posing for a group photo at the entrance to the Imperial Palace, Beijing. The picture of Mao Zedong, overlooking the sprawling Tiananmen Square in front of the palace, is so big that it can be seen from the other end of the square. Tiananmen Square is as large as 60 soccer fields put together.

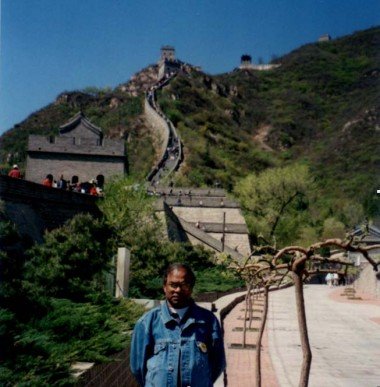

Photo-2:The author, on his way to the Great Wall of China.

Though the wall has a history of more than 2,000 years, most of it was built

during the rule of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The original purpose in

building it was to protect the empire from foreign invaders. Now it is one of

the greatest tourist attractions in China. In 1987, the UNESCO added the Great

Wall to its list of World Heritage Sites. Stretching from the Hushan Mountain

in the east to Jiayuguan Pass in the west, the wall passes through deserts,

grasslands, mountains and plateaus. Over

the years, many sections of the wall have deteriorated and disappeared. The

Badaling section of the wall, 43 miles northwest of Beijing, was rebuilt in the

late 1950s. One of the greatest thrills the author had during his tour of

Beijing was that, thanks to the rebuilding of the Badaling section, he was able

to walk at least half a mile on the 13,170-mile-long Great Wall of China.

(To be continued)

(M.P. Prabhakaran can be

reached at prabha@eastwestinquire.com)

7) Picture of a cow on Beijing billboard confuses a Hindu (Travel with MP Prabhakaran)

6) Yoga on Copacabana, conducted by a Brazilian beauty (Travel with MP Prabhakaran)

5

Hunchback and sugar loaf: Two tourist attractions in Rio de Janeiro

4)

How Portugal failed to colonize Calicut: Chat with a Brazilian

3) Brahma and Laxmi reincarnate in Brazil? (Travel with M.P. Prabhakaran)

2) Eva Peron’s tomb is too small for her ego (Travel with M.P. Prabhakaran)

1) My Two Embarrassing Moments in Buenos Aires (Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum-1: M. P. Prabhakaran)

http://dlatimes.com/article.php?id=40709

(about the author) An Indian Goes Around the World – I (Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum)http://dlatimes.com/article.php?id=40126