America

One of South Africa’s ruling class then, a migrant farm worker in Texas now (Travelogue ends)

(This is Chapter 25, which is also the last chapter, in Mr.

Prabhakaran’s book, An

Indian Goes Around the World – I: Capitalism Comes to Mao’s Mausoleum that we have been serializing in this space.

With this, we conclude the series. – Editor)

I landed in Johannesburg on a cool December morning in 2010. Though December is summertime in South Africa, it was unusually cool on the morning I landed there. My connection flight to Cape Town was at 12 noon, which meant that I had nearly four hours to kill, at the Johannesburg airport.

Cape Town was going to be the starting point of a seven-day tour of South Africa, organized by a travel company in New York. All 36 members of the tour group, all of them from the U.S., were going to meet at the Cape Town airport, to be escorted by a representative of the tour company.

After a 15-hour, nonstop flight from New York to Johannesburg, most of which I slept through, I badly needed a coffee. I headed to a nearby coffee shop, as soon as I completed immigration and customs formalities.

I was slightly disappointed to learn that the coffee would cost two U.S. dollars. That was as much as it cost me at New York’s JFK airport. In terms of per capita GDP, South Africa is 76th in the world. An item of daily consumption by an average South African costing as much as it does in the U.S., whose per capita GDP is sixth in the world, did come as a surprise to me. I decided to have it anyway.

There was another problem, though: The lowest-denomination dollar bill I had with me was that of 20. “Can I get the balance in U.S. dollars?†I asked the young lady at the cash register.

“No,†she said.

“In that case, can I get the same exchange rate as at any bank?â€

“No, we change it at 5.95 rand per dollar.â€

“That’s way below the official rate,†I told her. The official rate at the time was 6.83 South African rand per U.S. dollar.

She wanted to be helpful, however, and suggested that I go to a nearby bank and change the dollar. “You will get a better rate there,†she said.

But all the banks were inside the restricted area I had just come out of. A white South African was standing nearby watching what was going on.

“Let me pay for your coffee,†he said. “Just to pay for one coffee you don’t have to go back and go through all that trouble now. You can exchange your dollars in the city, later.â€

“Could you take this twenty-dollar bill and give me some rand?†I asked him. “I don’t mind losing money to another human being, especially one who is so generous to a total stranger.â€

“You can change the money later,†he said. “This coffee is on me. I insist.â€

“Thank you. Could I sit with you and chat? My flight, to Cape Town, is only at noon.â€

“My flight is at eleven-thirty. Let’s go and sit there,†he said, pointing to an empty table away from the sales counter.

“You might have thought that I was being petty,†I said, sitting at the table across from him. “It is not a question of how much the coffee costs or what the official dollar-to-rand exchange rate is. It has been my experience all over the world that when it comes to dealing with tourists, the price of everything goes up. I learned the hard way the need to be extra cautious.â€

“I offered to pay for the coffee,†he said, “because I didn’t want you to go back inside, looking for a bank or an ATM machine. You will have to go through the security formalities all over again. You and I know what a hassle it is.â€

“It’s very kind of you,†I said.

We introduced ourselves to each other and started talking. He was from a small rural community in South Africa, an hour’s flight from Johannesburg plus two hours’ drive from the airport. He did mention the name of his village and of the small town in which the airport is. I don’t remember them because I never heard of them before. He said he had just arrived from Washington, D.C.

From the way he spoke English, I could tell that he was not of British descent. I guessed that he was an Afrikaner, a white South African of Dutch descent. The Dutch were the first Europeans to colonize South Africa. The colonization began in the early 17th century. The English and the French followed later. The tiny, white Afrikaner minority ruled South Africa from 1948 to 1994. The political and social system which prevailed in the country during that period, and which enabled this 10-percent white minority to rule over the 90-percent non-white majority, was called – yes, you guessed it right – apartheid.

Apartheid Means ‘Apartness’

Apartheid in Afrikaans, one of the official languages of South Africa, means separateness or ‘apartness.’ Derived from the Dutch language, Afrikaans is the mother tongue of Afrikaners, who were the architects of apartheid. During the apartheid rule, all non-whites, especially the native blacks who constitute 80 percent of the population, were separated from positions of power and privileges and permanently relegated to an inferior status.

“What language do you speak at home?†I asked.

“Afrikaans,†he said.

“I guessed so,†I told him. “Did you go to the U.S. on a vacation?â€

“No,†he said, “I am a seasonal farm worker in Texas.â€

The answer came to me as a surprise. There are about 3.5 million seasonal farm workers in the U.S. Most of them are Latinos – from Mexico and nearby South American countries. I had never expected an Afrikaner, who had been part of the ruling class in South Africa until a few years earlier, to go all the way to the U.S. to take up job as a migrant farm worker.

Unlike most Latino workers who sneak into the U.S. during the farming season, however, he went there with proper documents. He showed me the temporary-worker visa stamped on his passport. He said that both the work on the Texas farm and the visa were arranged by a Johannesburg employment agency.

He was on his way home, after finishing his four-month stint. “This has been the pattern of my life in the past four years,†he said. “Work in Texas for four months. Come home and spend two months with my wife. Then back to Texas, again.â€

His wife was a school teacher. “We have no children,†he added. “Because I am a temporary worker, I didn’t want my wife to quit her job and join me in Texas. Moreover, there will be nothing left after feeding two mouths in the U.S. So we decided to put up with this arrangement for some time.†Back in his village, he had already bought a small piece of land. But “it will take years for the land to produce anything,†he said.

Another reason why he decided to leave his wife behind was that his work on the Texas farm was not conducive to any family life. He worked 16 hours a day, seven days a week.

“You have been working sixteen hours a day, every day, for four months!†I exclaimed.

“Yes,†he said, casually, giving me the impression that it was no big deal.

“You might have made a fortune in overtime.â€

“No, I get nine dollars an hour. No overtime.â€

“What?†I said, in shock, “I know nine dollars is more than the legal minimum wage in the U.S. But do you know that under the U.S. law, you are entitled to overtime for every hour you put in above forty hours every week?â€

“I heard something about overtime, but don’t know how much. I don’t know whether my employment agency in Johannesburg is collecting it. In any case, I wouldn’t fight for it. What I have now is a blessing, compared with what I was going through before I got it.â€

Before he became a migrant worker in Texas, he was jobless. Before he became jobless, he was the owner of a convenience store. “After the country came under black-majority rule, many black-owned stores came up in my village,†he said. “I started losing customers and money. When I could not take the loss any more, I decided to close my business. See, I am part of the three-percent white minority in my village.â€

I could discern some sadness in his tone when he uttered the last sentence. He continued: “After I closed my business, we survived on my wife’s income. In a way it’s good that we don’t have children. Otherwise, they would have suffered. You know people like me have no future in South African villages.†Once again, there was a tinge of sadness in his tone. “So when I saw an advertisement about this job, in a Johannesburg newspaper, I applied for it and got it. Maybe I got it because, years ago, as a teenager, I had worked on my father’s small farm. I did mention that experience in my application. My father declared bankruptcy even before I completed high school. Too much drinking. I couldn’t afford to go to college. So I opened a small store. That’s a long story.â€

Driving Truck on 16,000-Acre Farm

Soon after he arrived in Texas, he realized that the experience he had on his father’s farm, which produced fruits and vegetables, was not of much use. On the 16,000-acre Texas farm, which grows cotton and corn, everything is done on a mega-scale, with machines. So his new boss decided to use him as a truck driver. The owner didn’t live on the farm. He lived in Dallas. A supervisor, who lived on the farm with his wife and two children, ran the operation. “He shouts at us a lot,†he said. “But he is a good man.â€

The farm is near the southern border of Texas. “There were times when I fell asleep on the truck, almost hitting the fence that separates our farm from the neighboring one. Other times, I could let the truck run for miles and miles unattended, when I would be reading newspapers, preparing coffee, or eating my lunch.â€

The only time he and his fellow workers got a break during their four-month, 16-hour-a-day work was when it rained. Sometimes it rained for days and days, he said, when they would stay at home. That was the only time when they got a chance to use the living room, watch TV and chat with housemates. Twelve workers shared a house, which the farm-owner provided rent-free.

“We were not all that happy about the break we got,†he said, with a smile. “When we didn’t work, we didn’t get paid.†Sometimes, for several days in a row, they had to go without pay.

He planned to continue this grueling work pattern for four more years. It was his hope that if he endured it for another four years, he would be able to save enough money to buy a house. He planned to buy it in a nearby town and move there, after disposing of whatever he had in his village. “People like me have no future in the villages of South Africa,†he said, repeating the point he made earlier.

At that point, our conversation was interrupted by an announcement, asking passengers on his flight to proceed to the aircraft. I was disappointed that the conversation ended when it started to become interesting.

A Packet of Indian Biscuit as Parting Gift

I wanted to give him something as a parting gift. I couldn’t think of anything of value in my bag. I opened it and riffled through the contents anyway. Yes, there were two packets of biscuits among them. I took them out, opened one packet and shared it with him. To reassure him that it was safe to eat it, I started eating first.

“It’s good,†he said, tasting a biscuit himself.

I gave him the unopened packet and said, “Please share it with your wife when you reach home. I picked it up at an Indian store in my New York neighborhood.†Pointing to the word ‘Parle’ on the packet, I added, “It’s a famous company in India. This brand is very popular among Indians.â€

“It’s very kind of you,†he said, looking at the packet. He held it as though it were something precious. There was a glow on his face. “Yes, I will share it with my wife. I am sure she will like it.â€

We exchanged our email addresses and promised to stay in touch. I gave him a warm hug and said, “This conversation has been a real treat.â€

â—

Many things went through my mind, as I watched him walk toward the departure gate. I once again thought about the glow his face exuded when he held the packet of biscuit. Its material value was only a few cents. But the role it played in building a rapport between two total strangers, belonging to two totally different cultures, was invaluable.

I thought about apartheid, too. He being an Afrikaner, it was but natural for anyone to think about it. But I found it difficult to associate a fine human being like him with that much-detested system. The words he uttered sadly – “People like me have no future in the villages of South Africa†– reverberated in my mind. I asked myself: “Did the architects of apartheid ever imagine when they brought their country under that abominable system that, one day, some of their own would become its unintended victims? That some of those who once owned the land would one day be forced to leave it, looking for jobs as migrant farm workers in a foreign land?â€

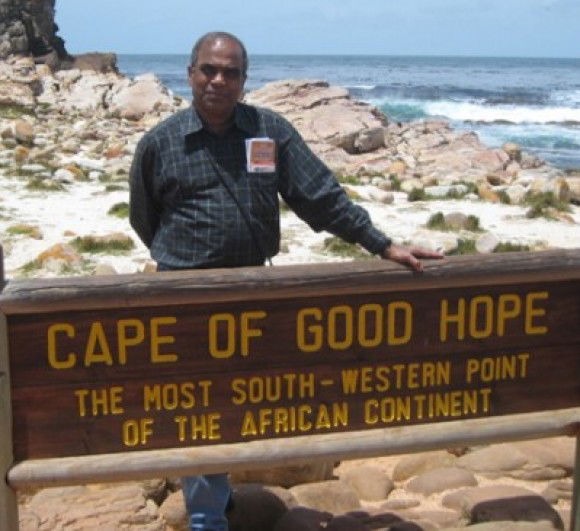

The author, at the Cape of Good Hope. He was an eighth-grade student in India when he learned for the first time that the first-ever rounding of the Cape of Good Hope by a human being was done in 1488, by a Portuguese navigator called Bartholomew Dias. The feat, he also learned, was accomplished in the course of Portugal’s search for a sea route to India, more specifically, a sea route to Calicut. For a thirteen-year-old, whose world did not extend beyond his village and the surrounding areas in Kerala, learning that a city just 60 miles from his home was the coveted destination of European powers, as far back as the 15th century, was indeed a thrilling experience. The first European power to launch trade expeditions to India was Portugal. And the first expedition was led by Vasco da Gama. He arrived at Calicut on May 20, 1498. All this went through the author’s mind when he stood at the Cape of Good Hope, on December 4, 2010.

(Concluded)

For earlier chapters: http://dlatimes.com/article.php?id=51001

(M. P. Prabhakaran can be reached by email at [email protected] or [email protected])

Two South Africans found an ingenious way of making a living: Entertaining tourists by demonstrating the art of man-to-seal, mouth-to-mouth fish-feeding.

Two South Africans found an ingenious way of making a living: Entertaining tourists by demonstrating the art of man-to-seal, mouth-to-mouth fish-feeding.