Articles features

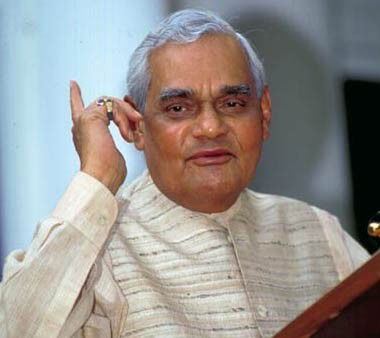

Will the BJP follow Vajpayee's 'raj dharma'? (Atal Bihari Vajpyee turns 91 on Friday)

The current mellow, accommodative outlook of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is in striking contrast to the provocative anti-minority postures of the 1990s, is the result of former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee's wisdom and sobriety.

On his 91st birth anniversary on December 25, it is necessary to remember that he single-handedly extricated the party from its potentially doomed predilection with majoritarianism, which is in sync with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh's (RSS) concept of a Hindu rashtra, where the minorities will be second class citizens.

But Vajpayee was a lone ranger who opposed this form of fascism and theocracy - not overtly or vociferously, for that was not his style - but unobtrusively and behind-the-scenes while making it clear to all and sundry that he could not be counted among Guru Golwalkar's loyal disciples although he maintained that he was essentially a pracharak (preacher).

It was because of the palpable distance between Vajpayee and the core ideas of the RSS/BJP that he came to be known as the right man in the wrong party while the fiery Sadhvi Rithambara, who once called for one big khoon-kharaba (communal outbreak) between Hindus and Muslims, described him as "half a Congressman".

"Why half," Vajpayee had asked jocularly when he heard of the Sadhvi's appellation for him. There was no sign of irritation or bitterness in his riposte just as he had told an interlocutor when informed about the Bajrang Dal's antics - "pagal hai" (they are mad) - half in jest and half with a sense of resignation.

The Gujarat riots of 2002 was however the real test of his statesmanship. As he told the state's chief minister of the time, Narendra Modi, who was known in that period as an uncompromising hardliner, that it was the bounden duty of the government to follow "raj dharma" or the ideals of a ruler which make no distinction between one category of citizens and another.

More than two decades later, Modi is now following this sage counsel because of his and his party's - though not of the RSS - realization that strict neutrality in the running of the administration is the only way to keep the multicultural, multi-religious, multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic country together.

Since Vajpayee knew this cardinal reality instinctively and reflected it in his personal life, he was able to achieve what no other leader has been able to do before or after him - run a 24-party coalition at the centre. Only a true proponent of raj dharma could have scaled such heights in accommodative politics.

It was the Gujarat riots which led to the unravelling of the coalition and ultimately to the BJP's defeat in 2004 - for which Vajpayee held the 2002 outbreak responsible.

Had the riots not taken place, there is little doubt that his coalition would have remained intact and that he would have won another term in office.

Although Vajpayee has now bowed out of public life, the standards he had set in the matter of communal amity have brought about a seminal change in the BJP's outlook. Not surprisingly, the first major sign of the change occurred in Gujarat where Modi organized his sadbhavna or goodwill missions soon after his victory in the 2007 assembly elections. Since then, as his description of the constitution as the country's one and only holy book shows, Modi has imbibed what Vajpayee said sitting by his side during a press conference in Ahmedabad in 2002.

Notwithstanding Modi's personal transformation from a hardliner to a moderate, not everyone in the BJP has unreservedly accepted Vajpayee's advice. There are still MPs and ordinary members who are Golwalkar's followers rather than Vajpayee's although Modi has been trying to rein them in.

It will obviously take time for everyone in the BJP to live up to Vajpayee's lofty examples in the matter of harmonious living in a country of 12 religions and 22 languages, as Modi recently told parliament.

Unless the party follows the former prime minister's ideals, it will not have much of a future in a pluralistic society which instinctively shuns extremism.

To students of contemporary politics, the question will remain whether Vajpayee should have tried harder to inculcate his conciliatory message in the saffron brotherhood comprising the RSS, BJP, Vishwa Hindu Parishad, Bajrang Dal and others during his days in power (1998-2004).

If anyone in the Sangh Parivar could have done so, it was him because of his high stature and unassailable prestige. But such an endeavour would have meant taking on the hawks in a frontal confrontation to turn them away from their fascistic, anti-minority weltanschauung which they have followed since the 1920s.

Vajpayee was temperamentally not ready for such a battle. In the 1990s, it was enough for him to have lifted the BJP by the bootstraps to bring it to the centre-stage of politics from the margins, where it had languished for decades. This feat was something which only Vajpayee could have accomplished because of his wide acceptability across the political spectrum. For him to have battled the RSS, too, would have been too much.

But it is a task which someone in the BJP would have to take up sooner or later if the party wants to be a long-distance runner in Indian politics.

14 hours ago

'This is a long-term plan, a strong desire to return to the old life'; Usha Vance

14 hours ago

AAPI President Dr. Amit Chakrabarty Strengthens Community Bonds with Chapter Visits

15 hours ago

Indian envoy, US Congressman discuss shared priorities on defence and security cooperation, AI

15 hours ago

Indian American leaders urge deeper political engagement at Detroit dialogue panel

15 hours ago

US Congressman calls for deeper India–US ties, civic engagement

15 hours ago

Manhunt intensifies for Brown University shooter, campus on lockdown

15 hours ago

Two US soldiers, translator killed in ISIS attack in Syria; Trump vows ‘serious retaliation’

15 hours ago

US Air Force completes recovery operation of crashed MQ-9 drone

15 hours ago

At least two killed in shooting at Brown University in US Rhode Island

15 hours ago

CM Stalin to attend DMK youth wing’s regional conference in Tiruvannamalai today

15 hours ago

Polling underway for second phase of panchayat elections in Telangana

15 hours ago

PM Modi likely to celebrate Pongal with farmers during January TN visit

15 hours ago

Water storage in TN's Cauvery delta tanks increases as rain boosts water storage