Articles features

In the jaundiced world-view of British fiction, Brexit was preordained

Britain on Friday voted to leave the European Union after a 43-year-long stint. But it had less than smooth relations with the group of nations -- its first application to join was peremptorily rejected by France's Charles De Gaulle in 1963, dealing a major blow to the career of then Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

It was only in 1973 that it got in (under Edward Heath, another Conservative) but never seemed to have been comfortable there given the less than complimentary references in popular media.

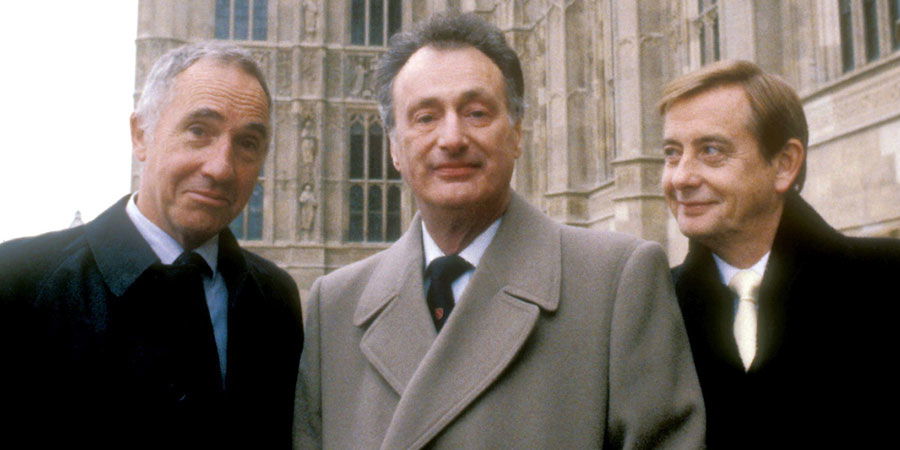

One of the best guides to what the British establishment thought of their European association is in Anthony Jay and Jonathan Lynn's satirical TV sitcom "Yes Minister" (1980-84) and "Yes Prime Minister" (1986-88). Though it chronicled Minister for Administrative Affairs Jim Hacker's struggles to effect changes in government policy against the Civil Service's opposition, represented particularly by his Permanent Secretary, Sir Humphrey Appleby, dealing with outcomes of Britain's membership of the European Economic Community (as the European Union was till 1993) frequently came up.

Hacker initially had a benign view of Europe but Appleby was more cynical.

In one episode, "The Writing on the Wall" (telecast March 1980), he tells Hacker that "Britain has had the same foreign policy objective for at least the last five hundred years: to create a disunited Europe", for which they had "fought with the Dutch against the Spanish, with the Germans against the French (Napoleonic Wars), with the French and Italians against the Germans (World War I), and with the French against the Germans and Italians (World War II). Divide and rule, you see. Why should we change now, when it's worked so well?"

As Hacker notes it was "all ancient history", he responds: "Yes, and current policy. We 'had' to break the whole thing (the EEC) up, so we had to get inside. We tried to break it up from the outside, but that wouldn't work. Now that we're inside we can make a complete pig's breakfast of the whole thing: set the Germans against the French, the French against the Italians, the Italians against the Dutch... The Foreign Office is terribly pleased; it's just like old times."

On a policy for a national identity card, Appleby notes that the "Germans will love it, the French will ignore it and the Italians and the Irish will be too chaotic to enforce it. Only the British will resent it".

In a latter episode ("Devil You Know", telecast March 1981), as Hacker says "Europe is a community of nations, dedicated towards one goal", Appleby laughs and asks him to look at it "objectively".

To Hacker's assertion that Britain joined "to strengthen the brotherhood of free Western nations", Appleby responds: "We went in to screw the French by splitting them off from the Germans." In the same episode, he seeks to explain the reason for some EU directive they have to follow as "the penalty we have to pay for trying to pretend that we're Europeans".

"Party Games" (telecast December 1984), which sees Hacker's unlikely elevation to the top post, begins with him trying to deal with the "Eurosausage" - the latest European standardisation measure which will see the British sausage now be called the "Emulsified High-Fat Offal Tube" and adroitly use the issue to gain enough popularity to succeed the Prime Minister who has resigned unexpectedly.

Though a compromise is reached on the sausage issue, Hacker pretends it still hangs and attacks Europe in a speech: "I'm a good European. I believe in Europe. I believe in the European ideal..... but this does not mean that we have to bow the knee to every directive from every little bureaucratic Bonaparte in Brussels...... They've turned our pints into litres and our yards into metres; we gave up the tanner and the threepenny bit, the two bob piece and the half crown. But they cannot and will not destroy the British sausage."

Attitudes haven't changed much since. BBC journalist-cum-author Adam Brookes, in his second espionage thriller "Spy Games" (2016) tells us that while British intelligence share an important document with their American, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand counterparts, only a "stripped-down version, scrubbed almost into invisibility, went to the European Union Situation Centre in Brussels."

(Vikas Datta is an Associate Editor at IANS. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)