Health

Seasonal flu may increase risk of Parkinson's disease

New York, May 31: Researchers have found evidence that environmental factors, including infection with influenza, may increase risk of developing Parkinson's disease.

Most cases of Parkinson's have no known cause, and researchers continue to debate and study possible factors that may contribute to the disease.

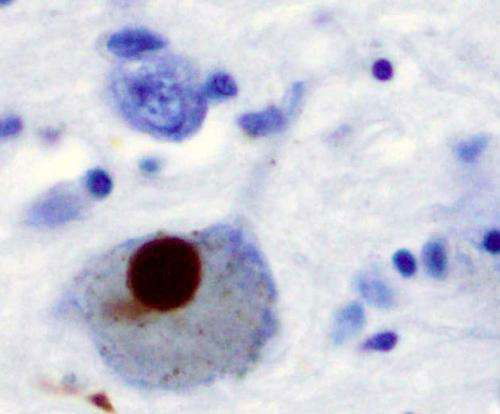

The new study published in the journal npj Parkinson's Disease showed that a certain strain of influenza virus predisposes mice to developing pathologies that mimic those seen in Parkinson's disease.

"Here we demonstrate that even mice who fully recover from the H1N1 influenza virus responsible for the previous pandemic (also called 'swine flu') are later more susceptible to chemical toxins known to trigger Parkinson's in the lab," said Richard Smeyne, Professor at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, US.

Previously, the researchers showed that a deadly H5N1 strain of influenza (so-called Bird Flu) that has a high mortality rate was able to infect nerve cells, travel to the brain, and cause inflammation that, the researchers showed, would later result in Parkinson's-like symptoms in mice.

Inflammation in the brain that does not resolve appropriately, such as after traumatic injury to head, has also been linked to Parkinson's.

Building on that work, the current paper looked at a less lethal strain, the H1N1 "swine flu," that does not infect neurons, but which, the researchers showed, still caused inflammation in the brain via inflammatory chemicals or cytokines released by immune cells involved in fighting the infection.

Using a model of Parkinson's disease in which the toxin MPTP induces Parkinson's-like symptoms in humans and mice, Smeyne showed that mice infected with H1N1, even long after the initial infection, had more severe Parkinson's symptoms than those who had not been infected with the flu.

Importantly, when mice were vaccinated against the H1N1, or were given antiviral medications such as Tamiflu at the time of flu infection, the increased sensitivity to MPTP was eliminated.

"The H1N1 virus that we studied belongs to the family of Type A influenzas, which we are exposed to on a yearly basis," Smeyne said.

"Although the work presented here has yet to be replicated in humans, we believe it provides good reason to investigate this relationship further in light of the simple and potentially powerful impact that seasonal flu vaccination could have on long-term brain health," Smeyne added.