Health

Alzheimer's patients may benefit from cell therapy

New York, March 17: Transplanting a special type of neuron into the Alzheimer's brain can restore memory and other cognitive functions, a study has revealed that can lead to new treatment.

The brain relies on the perfect coordination of many elements to function properly. If one of those elements is affected, it affects the entire body.

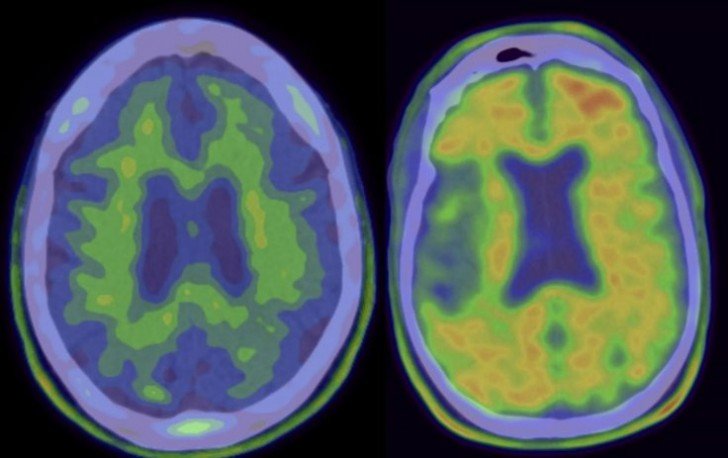

In Alzheimer's disease, damage to specific neurons alter brainwave rhythms causing a loss of cognitive functions.

The inhibitory interneuron is particularly important for managing brain rhythms, said researchers at Gladstone Institutes in the US.

The scientists uncovered the therapeutic benefits of genetically improved interneurons by transplanting them into the brain of a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.

The inhibitory interneuron controls complex networks between neurons, allowing them to send signals to one another in a harmonised way. They are responsible for the instructions given by the brain.

An imbalance between these two types of neurons creates disharmony and is seen in multiple neurological and psychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, schizophrenia and autism.

Researchers noted in Alzheimer's mouse models that the inhibitory interneurons do not work properly.

However, when the enhanced by adding a protein called Nav1.1, the interneurons with enhanced function are able to overcome the toxic diseased environment and restore brain function.

They are then able to properly control the activity of excitatory cells and restore brain rhythms, the researchers noted.

"We took advantage of the fact that transplanted interneurons can integrate remarkably well into new brain tissues, and that each interneuron can control thousands of excitatory neurons," said Jorge Palop, Assistant Professor at the University of California in San Francisco, the US.

"These properties make interneurons a promising therapeutic target for cognitive disorders associated with brain rhythm abnormalities and epileptic activity," Palop added, in a paper published in the journal Neuron.