Articles features

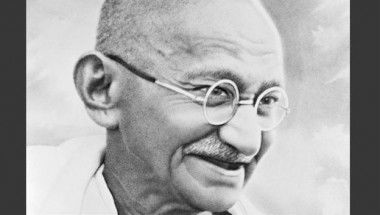

Rediscovering Mahatma Gandhi in this globalised age

It's almost a month since British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond

visited India, a few days before Mahatma Gandhi's statue was unveiled at

Parliament Square in London in the presence of Union Finance Minister

Arun Jaitley. Call it a coincidence, the visit was appropriately timed

on March 12, the day 85 years ago when Gandhi launched his mass

satyagraha movement from Sabarmati in Gujarat to the banks of the Dandi

to break the unjust salt law that, to a large extent, signalled the

beginning of the end of the British Raj in India. It was at this point

of time Gandhi drew world sympathy in this (non-violent) battle for

'right against might'.

One could argue that though the mass civil

disobedience movements - a term borrowed by Gandhi from Henry David

Thoreau, a 19th-century American writer and used as 'satyagraha' in the

Indian context - led by Gandhi to end the monopoly of the British Empire

upon the Indians did not produce a constitutional change, it

demonstrated that ordinary Indians had the power to drive events. In

several parts of India, nationalists succeeded in weakening the

forcefully imposed/established structures. Moreover, people began to

defy - as well as challenge - the injustices.

Peter Ackerman and

Jack DuVall write in their book, "A Force More Powerful: A Century of

Nonviolent Conflict": "While the campaign did not wreck the raj, it did

succeed in shredding the legitimacy of British rule. For over a century

the regime had represented itself as benign, standing for sound economy

and gradual reform - and likely to bring home rule in the long run. As

long as Indians went about their business and cooperated with its laws

and institutions, the British could maintain this façade. But civil

disobedience shattered it".

And the greatest example of this was

the Salt March that brought people from different classes and regions -

wherever Gandhi made his presence and from further distance too - and

forged a durable link among Indians who put aside their personal

interest to promote national interest. Mahatma Gandhi became the

embodiment of national purpose for millions of Indians who nonviolently

fought for 'truth force' vis-Ã -vis 'brute force'.

And here was

Philip Hammond addressing the media on Britain's growing relations with

India. Referring to the unveiling, Hammond said: "That statue will be a

tribute to the inspiration Gandhi provided not only to India but to the

people of the world", adding, "It is fitting that the man (Mahatma

Gandhi) who founded the world's largest democracy should look across the

Square at the world's oldest parliament (in Britain)".

This

would be a befitting acknowledgement - rather than tribute - to a man

who as an 18-year-old touched upon a land which threw before him an

entirely different world (19th century England). Never in his life, had

he seen something so splendid, so ornate and so polished that made the

young Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi abandon his habitual modesty to present

himself as an English gentleman, what author Robert Payne in his book

"The Life and Death of Mahatma Gandhi" calls as an 'infatuation', which

ultimately would pass.

It cannot altogether be denied that the

British recognized the good points in a rebel and it was worthy. As the

English journalist, novelist and educator Edmund Candler recorded in

1922: "Gandhi's honesty of purpose has been generally admitted by the

Indian Government, by the Viceroy, as well as by the Secretary of State.

The rage of a certain section of the British press with Mr. Montagu,

when he admitted that Mahatma Gandhi was his friend, is understandable".

In

the 67 years - after Gandhi's death - that separate us from him,

humanity has witnessed breathtaking achievements in science and

technology and even the texture and rhythm of our life have been

altered. Some see it as a model of development; others perceive it as a

race against time.

As India celebrates the 100 years of Gandhi's

return from South Africa (1915-2015) and gears up for the centenary

celebrations of the historic 'Champaran Satyagraha' in 2017, the

satyagrahi Gandhi seems to be little awed by the dynamism of the events

that are to unfold as the clock progresses. For the Gandhi who returned

in 1915 saw India as a whole and not in parts and fragmented, if not

externally to the world, yet too demanding.

The culture wars

occurring in the multicultural societies - and India is an integral part

- is just a microcosm of the global conflict. No country today seems to

have been left untouched by the phenomenon of violence. The world -

because of frequent confrontations and violent eruptions despite the

rapid and globalised progress - has become a one physical unit, but not

an integrated entity.

While rediscovering - and more so

repackaging Mahatma Gandhi in this globalised era - it will be apt to

realize - and adhere - that the spirit and legacy of Gandhi demand bold,

courageous and connected initiatives which reach the last man in

society. The spiritual Gandhi has today become not only a national

leader but a missionary of civilization. Or is it that the repackaging

has transformed this mass leader into a façade, which only exists but

dissipates?

Also to the unimaginative - or the disbelievers - the

Mahatma remains insincere or insignificant. Can a remoulded Gandhi be a

guiding force to the East and the West alike, as the crisis of

civilization sharpens its edge and as Gandhi stands as a significant

figure at the world's crossroads?

(Rajdeep Pathak is programme

executive at New Delhi's Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti. The views

expressed are personal. He can be contacted at rajdeep.pathak@gmail.com )